Chris and I got into fostering dogs after Chris’ coworker had shared her experiences with him. Alaina had always been interested in the idea, and had convinced him years earlier to foster cats. Once they reached full cat capacity (two), and partial dog capacity (one of two), Chris was open to the idea of one more canine in the house. Knowing someone that actively fostered dogs helped him understand the undertaking and also gave us some security, since we had a first-hand resource to help.

We started with the rescue that our resident dog, Juniper, came to us from. American Black and Tan Coonhound Rescue (ABTCR) has a mission to rescue coonhounds and bloodhounds all across the United States. Juniper came to us from Alabama, for example, and we were set to foster in Pennsylvania. We filled out a form, had a phone interview, sent pictures of our home, and were eventually approved! First step done. We also ended up reaching out to a local(ish) rescue, Northeast Coonhound Rescue (NECR), whose mission is to rescue coonhounds and beagles into the Northeast United States. Both organizations required forms (personal information, experience, references) and interviews as part of the approval process.

We had our first foster through ABTCR, in March of 2019. You can check out all the fosters that have passed through our home at our website page, Coonhounds.

Instead of walking through each individual foster experience, I want to outline things that don’t change from foster to foster.

Introductions

We have two resident cats and one resident dog at HnH. It is important that the safety of our resident pets is not compromised by our foster dog. We cover this by requesting the foster is ‘cat tested’ and ‘dog tested’ in a safe, supervised environment wherever they come to us from (shelters or a volunteer’s home). We also don’t set them up for failure.

Introductions to the resident dog happen through a gate or fence. The foster is on a leash outside the fence, then we let Juniper out in our backyard. They may interact through the fence, safely separated. We also let the foster dog explore the yard on their own. On the leash we take them around the backyard and let them sniff all the sniffs, get to know the scents of the animals here. Thankfully, with much experience, we know Juniper is safe around new dogs. We let Juniper out into the yard, assuming all has gone well, and they meet, foster dog still on the leash. 100% of the time, the foster has been enthusiastic about wanting to play and eager to run around with Juniper. We’ll let the foster off leash and let the dogs run around together. Juniper is a rock star, in that while she tolerates bad manners, she corrects them. She is not aggressive when manners or her wishes are violated, but she enforces her boundaries. She teaches the fosters dog manners and good play practices.

Introductions with the cats happen similarly inside the home. Resident animals are removed, and the foster is allowed to get to know the space and the smells. We put up a gate with a cat-door in it, that allows the cats to have several rooms to themselves. This allows them access to safety and alone time, as needed. Their litter is always only accessible to them, not the foster. The foster dog will spend the first few days being leashed while inside so they can get to know the cats and we can work with them on potty training. One cat is very people shy, but pays dogs no mind. They can smell her, and she may hiss, but generally doesn’t run away or further react. Our other cat is the king of the house, and knows it! He will not like the intruder at first, so it’s slow introductions, removing the dog fairly quickly from his bubble, and ensuring the foster dog exists in the home, but not in the cat’s space. As the resident cat warms up, there’s constant supervision. The foster dog is never left unattended, which is where the dog room (next section) comes in useful. With each foster, we have reached a balance among the resident pets, even the King Cat. Not everyone is thrilled, but everyone can coexist.

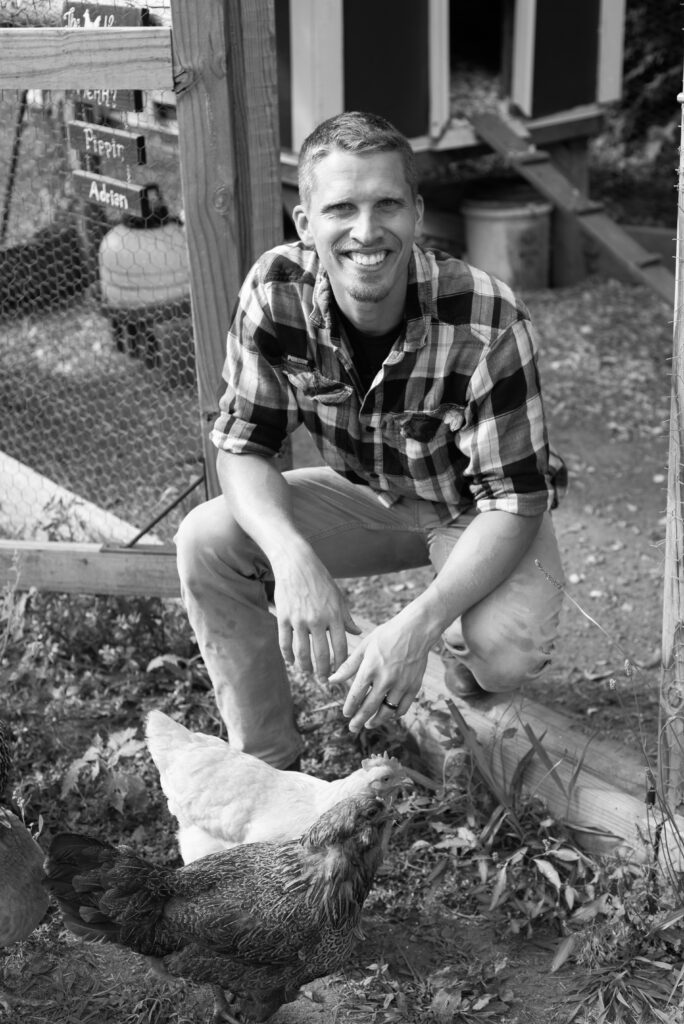

Note: We do have a flock of chickens, and foster dogs are never given access to the chickens.

The Dog Room

In our first house and in our current home, we provided a room for the foster dog. The room included a dog crate, dog bed, blanket, food and water dishes, and dog toys. In our first home, it was also our office space so there was an old desk, desk chair, and filing cabinet also in the room. In the current house, this space is the mud/laundry room so there it a washing machine, dryer, and trash can (with lid) in the space. The office space had a full door, and the mud room came with a half-door already. The expectation of this room was low. The floors must easily be cleaned, anything in the room is not of high value/can be replaced (including the window treatments and molding), and the room must be safe for the dog. It is important to have a “dog-proof” place the dog may be left alone. This place serves many purposes. If you need to leave the house, the dog may stay here. If there’s a contentious relationship between the resident pets, the dog may stay here (“crate and rotate” type scenario). The dog should come to view this place as safe, so as they emotionally need a ‘home base’ they have one.

The Crate

I won’t go completely into crate training, but you may assuredly find many great resources for insight into crate training (libraries, internet, etc.) and the benefits. Our foster dogs sleep in their crate, and are not crated during the day. We also believe crating at night helps with potty training. The right size crate will be humane, allowing them to stand and turn around, but also discourage elimination in the space. The crate is not used as a punishment. We feed them breakfast and dinner in the crate, to associate rewards with the crate. That is the fastest way we have found to get fosters into the crate: food/treats. With our most recent foster, toys were the key (throw a toy or two in there and he’d run in after them). We use the same command when they enter the crate for bedtime “go home.” Ultimately, we want to set the dog up for success, and being crate trained adds to their resume.

Behavior

After the dog becomes accustomed to their room and routine, we start working on training. “Sit” has generally been easily mastered. “Down” is a fairly easy progression. We have also successfully trained a wait, with release word “okay” several times. We do this by starting with their meals. Instead of food waiting for them in the crate, we graduate to asking them to be in their crate, then delivering the food. We want to communicate you need to be in your crate, then you are provided the meal, still in the crate. We graduate this to be in the crate, and stay there until I set the food down, outside the crate. This is reinforced by simply repeating the steps. If the dog leaves the crate before the food is down, we make an “ah, ah” clear verbal communication, and pick the food up. Ask them to come back to the crate, and repeat. Obviously this isn’t nailed on the first try, but it’s important to acknowledge success immediately. Use a success/release word, which will help in future steps. We like “okay!” Right when the food hits the floor, when they are still in their crate, they get an “okay!” Keep eye contact, and be consistent in the expectation of this step. We have found all fosters have been quick to understand this. The last step is the wait. It is similar in reinforcement, where we use the verbal “ah, ah” for not yet and withhold “okay” until the release. Now the word is the trigger alone. We set the food down on the floor, outside the crate, and expect the dog to wait for the “okay” to leave the crate and eat. Teaching them patience goes so far in other behaviors and training. With hounds generally being incredibly food motivated, this training regimen has been very effective.

Outside of commands, other behaviors we reinforce are no foster dogs on the furniture. Again, this makes their resume longer, as they may go to a family that practices that. We use positive reinforcement training, so the best practice is to reward good behavior with treats or attention. Bad behavior is addressed with stern verbal communication “no” and redirection (treats, toys, attention). Our current foster, as I write this, seems to have learned his name, so he has been easy to redirect by calling him and lavishing him with attention as his reward. This is how chewing or handling non-dog items are handled. It’s important, again, to set them up for success and limit access to items they shouldn’t have. We take responsibility for adapting our space, which might mean moving a shoe rack, making sure shelving is higher off the ground, or enforcing a boundary on our bedroom.

Potty training has worked the same with all the fosters. We elect to foster older dogs more often than not, which we know are physically capable of holding their bladders for longer. It’s just down to communicating where they may eliminate (outside) and where they may not (inside). We do not utilize puppy pads. As mentioned above, we keep a leash on them while potty training, or what we graduate to is a harness with a short handle for easy grabbing. When not in the dog room they are supervised. If they start to eliminate, we catch them in the act and startle them with a loud noise “hey hey hey,” “AYYYY,” or “ARGHS,” whatever works, the idea is to surprise them a bit, so they may stop eliminating. Then you act fast! grab the handle and get them outside!! Walk around with them until they finish eliminating, and reward. Amazing! Treats! Positive reinforcement. Being proactive helps as well: supervise their outdoor time and put a name to the behavior (we choose “go potty”) and reward when that naturally occurs outside. Also noteworthy, is that if the foster dog eliminates in their room, when unattended, we do not address it with them. The mess is cleaned, and that’s that. We reinforce behavior in the act, good or bad, not after the fact. Similar to training at meal times, we have found our fosters have been potty trained fairly quickly, then we no longer need the harness inside.

We also like to reinforce their names by giving them and Juniper treats while verbalizing their name. “Juniper” as I hand Juniper a treat avoiding the foster, “NAME” when handing the foster their treat. Juniper is always close by, and can also model the requested behavior (“sit,” “down,” etc.).

Other Notes

We ask many questions before the fosters come to stay with us, including about cat/dog friendliness, as mentioned earlier. We also ask where they are from, the condition they are in, how they came to the rescue, how their handlers observe their behavior to be. We have yet to turn down a dog due to the answers (we have had varying cat-test answers), but we like having the context. We also get all their vet records with them, when they arrive.

We feed the dogs the same food as our resident dog gets, and at the same time, though separately in the dog room. Juniper eats in the kitchen, the dog room comes in handy to avoid food aggression, and let the slower eater take their time without intrusion. Food, treats, and toys are all expenses we manage as part of the fostering process.

Sometimes we see the vet, as needed, with fosters, in which case we take them to the same vet we use. We communicate with the rescue because the rescues we work with cover medical expenses. We also communicate with the rescues regarding preventative medicine, as they send that along as well, so the fosters are given what we receive.

We also got an “ADOPT ME” collar and leash set from Amazon, that we put a tag on with our information. Every foster we have had has used it, and it really helps attract attention when we take the dogs out. We also carry rescue business cards, so we can put the dog’s name on the back and pass them out to potential adopters. This hasn’t worked yet, but has led us to meeting many interesting people, and socializing the rescues!

Expectations

The last bit I’ll touch on is that while fostering a dog, your day-to-day will not be the same as when you are not fostering a dog. I wake up earlier, knowing the morning routine with a foster takes longer. Sometimes our fosters whine at night, until they adjust to their routine. Supervising them requires constant vigilance, which is not my normal state of existing in my home. Everyone asks “how can you let them leave?” and sometimes the answer is as simple as so I can have my life back.

Our resident dog is six, and has been with us for almost five years. We can walk with her off-leash, we can let her be out with our chickens, and she sleeps an awful lot. She doesn’t lick or counter surf, or chew things she shouldn’t. This makes for a very easy life with her, where I really never have to be on my guard. Starting with a new dog from scratch requires work. Many of the dogs that we have fostered have challenged us, with separation anxiety being the hardest to manage. All of the dogs have changed our day-to-day lives. And all of the dogs have loved us unconditionally, too.

Fostering Dogs 101 Summary

Plan introductions to resident pets

Set up a safe space for the foster

Reinforce behavior expectations

Work on light training

Manage your expectations

I hope this has provided some insight into the experience of fostering dogs!! We believe it is all worth it, and all the above has worked for us many times. If you have any questions, please comment below or email us at hopsnhoundsfarm@gmail.com. We would love to support anyone else considering fostering, as rescuing animals is a strong value of ours.

Cheers and Howls,

Alaina